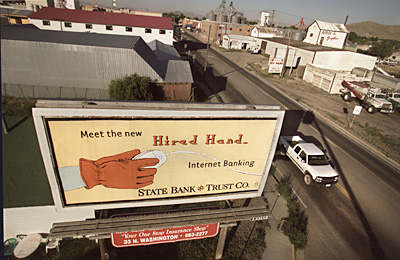

For Paul Rebich, a connection with the past is never far away. On any given day, four

generations of Rebich family history are right under his feet. For a hundred years, cattle

bearing his family's O-Bar-R brand have grazed the same fields just south of Dillon,

Montana. The rhythm of his work -- from calving season to haying season and back again --

is largely unchanged from his great-grandfather's time.

The 27-year-old rancher's future is also right here. In the trailer he and his wife

call home, he's slowly building an international cattle-breeding operation -- on the Net.

Ultimately, Rebich would like to run a Web-based, breeder-to-breeder virtual marketplace.

Technology of one sort or another has been at home here for a long time. For previous

generations, rural electrification and telephones spelled comfort, convenience and

economic opportunity. Today, the Internet is slowly creeping into the daily life of

Dillon, where an estimated 35 percent of the 4,004 residents are online.

While some in this cattle town see the Net as just one more strike against a hard-won

way of life, Rebich and others are finding novel ways to have the ``Big Sky'' lifestyle

and a digital future. In this corner of paradise, a tech revolution is

quietly being fought one person at a time.

Southwestern Montana is not an easy place to make a living. Rebich, who routinely puts

in 12-hour days on the ranch, pays himself a salary of $800 a month. It's no mystery why

he would hustle so hard to have a life here:

Beaverhead County, cradled on three sides by the Continental Divide, is one of the last

best unspoiled regions of a state that calls itself ``The Last Best Place.'' The trophy

trout, the alpine meadows so green they'll make your eyes ache, the whole ``Big Sky

Country'' riff -- it's all true.

|

|

| In the middle of a wheat field,

road crews install fiber optic cable that will help provide Internet service to the rural

West, where national Internet service providers like America Online and Earthlink are not

available. |

|

Hand-sewn dustcovers

Two retired teachers launch Dillon-Net

Ken and Nellie Bandelier spent much of their careers in Dillon working on the bleeding

edge of computing. Between the two of them, you could say they have more than 40 years of

accumulated geekitude. Nellie, a former elementary school teacher, and Ken, a former

biology professor at Western Montana College in Dillon, were both using computers in their

classrooms back in the bad old days when the only educational software available was the

stuff you wrote yourself.

|

|

| Dillon-Net founder Nellie

Bandelier helps a young client with e-mail at the agency's main office. |

|

After the Bandeliers retired in 1988, Ken kept a hand in the digital world. Five years

ago, after they secured a home dial-up Internet account through the college, Nellie

started writing an Internet column for the Dillon Tribune. Before long, she was inviting

readers to meet at her house to share ideas about how the Net might help their community.

Less than a year after Nellie started the column, the Bandeliers launched Dillon-Net

with a single computer donated by United Way.

Today the community technology center provides public-access terminals and training at

10 sites in town and 14 locations in nine outlying communities. The smallest Dillon-Net

outpost is in the school in the town of Grant (population: 6). In truth, Dillon-Net is

more of a loose confederation than a network. The central office of Dillon-Net supplies

basic training and some ongoing support, but each individual outpost must provide

everything else -- volunteers, Internet service and electricity. The central

organization's annual budget: $10,000.

The shoestring success has not escaped notice in the world beyond southwestern Montana.

Dillon-Net has been a finalist two years running in the AOL Foundation's Rural

Telecommunications Leadership Awards. It has also picked up honors in a Swedish telecom

project competition.

Dillon-Net central is two rooms in the back of the ``English Professional Building,'' a

reconfigured cinder-block gas station now shared by a doctor, a dentist and an

optometrist. Like just about every other private non-profit in the country, it's

overcrowded with mismatched hand-me-down furniture. The seven computers -- each of which

sports its own dustcover hand-sewn by students at the high school -- all share a single

56K data line.

|

|

| Dillon-Net co-founder Ken

Bandelier performs some maintenance outside Dilllon-Net headquarters. |

|

About 100 Dillon residents get individualized help at the main office each week. The

Dillon-Net style of instruction could best be characterized as viral: A volunteer shows a

new Web-authoring trick or application to Nellie, who teaches one of the schoolkids who

are usually hanging out in the afternoon, who teaches the local artist, who teaches

. . .

``A lot of people who walk through that door have never touched a computer before,''

says Glenna King, the local United Way executive director, who puts in weekly stints as a

Dillon-Net volunteer. ``They say: `I want to get on the Internet. Can we do that today?'

We can try. We start by learning how to work the mouse.''

Buying tractor parts

'The Big Hole' meets the killer app

To see a community that's considered remote by Montana standards, head west from Dillon

over 40 miles of sometimes-paved road, cross two mountain passes and drop into the Big

Hole Valley, referred to by everyone hereabouts as simply ``The Big Hole.'' When you see

some buildings by the side of the road, you are in downtown Jackson (population: 35 people

and 18 dogs). On the left, in the weathered 103-year-old IOOF hall, lives the Big Hole's

ambassador to the digital world, Judy Halazon.

Halazon, a successful graphic artist until multiple health problems put her on permanent

disability in 1994, met Nellie Bandelier four years ago, just as Dillon-Net was taking

off. ``I'd never even turned a computer on -- not any computer,'' she recalls.

``And I just looked at her for the longest time and thought, `C'mon, honey, this is not my

ball of wax.' '' But it was. A basic Windows PC in the corner of Halazon's joyously

cluttered living room is Jackson's Dillon-Net outpost.

Halazon, a successful graphic artist until multiple health problems put her on permanent

disability in 1994, met Nellie Bandelier four years ago, just as Dillon-Net was taking

off. ``I'd never even turned a computer on -- not any computer,'' she recalls.

``And I just looked at her for the longest time and thought, `C'mon, honey, this is not my

ball of wax.' '' But it was. A basic Windows PC in the corner of Halazon's joyously

cluttered living room is Jackson's Dillon-Net outpost.

At the ragged edge of civilization, in places like the Big Hole, it is flat-out

impossible to get away from humanity. You don't have to like your neighbors, but you need

them. People watch out for each others' kids and animals. Literally or figuratively,

Jackson's residents mind their neighbor's business. ``Everybody helps everybody out

here,'' says Halazon.

Over four years, Halazon has found a new role for herself as the den mother to the Big

Hole's budding digital elite. Ranch families from up and down the valley, migrant workers

and bike tourists passing through the region all rely on her for guidance and a line out

to cyberspace. When they can't come into town, they call and Halazon reads them their

e-mail.

|

|

| Many ranch families rely on Judy

Halazon, left, for their link to the Internet. When they can't come to Jackson, Mont., to

see her in person, they call and Halazon reads them their e-mail. |

|

``It gives me something to do,'' says Halazon. ``When I first started this, with the

multiple sclerosis, I didn't know if I'd get the hands back. I couldn't get up and down

the stairs. There was a lot of information and support on the Internet. I'm one of the

lucky ones with remitting MS that might never come back again.''

Halazon's unpaid job is to make the Internet relevant in a place where the main

enterprises -- chasing cows and putting up hay -- haven't changed very much since the

arrival of the telegraph. She's been called on to advise and assist on everything from

marketing the work of local craftspeople to relaying messages for stranded travelers.

|

|

| Judy Halazon mans the Cyberian

Outpost, 40 miles west of Dillon. |

|

Although it took a couple of years for Jackson to warm to the Internet, the word is out

that this is something of practical value. A killer app for the typical Dillon-Net

customer in the Big Hole: express-shipped tractor parts. ``It's sinking in with people

that they can get a better price, they can see what they're getting and they don't have to

waste the time driving,'' says Halazon. ``With these tractors, some are 2 years old, some

20 years old, 15 different brands, and when something goes haywire you end up calling all

over the country trying to fix it. Bingo, you get it on the Internet and it just amazes

them.''

At the time Halazon set up shop she knew of just three Internet-connected computers in

the Big Hole, which she guesses has a population of about 150. Now, she figures 25 or 30

residents who used to rely on the Dillon-Net machine have gone on to procure their own.

|

|

|

Judy

Halazon chats with a neighbor in the tiny burg of Jackson, a suburb of Dillon. |

Halazon's Dillon-Net outpost cost $1,674 to operate in 1999 -- most of that going to

paper and printer cartridges. Internet access and phone charges through the local

mom-and-pop operator, Southern Montana Telephone, run $32 a month. She gets about $75 a

year in donations. The rest is out of her pocket. As she is quick to point out, people are

used to getting by under less-than-ideal conditions out here. She does wish she could get

more RAM, though. She's been waiting six months and there just isn't anyone to make the

drive out from Dillon to put it in.

Online 'revelations'

Ranch job hunt; shoppers have choices

As is probably the case in the rest of America, the No. 1 driver for getting rural

residents to make that initial foray into the wired life is family communication. Digital

culture amplifies and extends networks that are already important in people's lives.

And right behind family e-mail is shopping. It would be hard to overestimate just how

much of a social leveler e-commerce has been for rural folk who have never had access to

the selection and competitive pricing of suburban malls. When a routine shopping trip to

Butte, 40 miles away, can burn half a day, as one Dillon resident put it, ``you get to

love Amazon. To be able to get a book in two days is almost a revelation in this town.''

Halazon says the Net has particular value for the ranch hands who typically work six

days a week and often lack the transportation to get into even Dillon. ``It's either rich

or poor here, there's no in-between in this area. You either own the ranches or you work

on them,'' she says. ``I have ranch hands -- they generally make $400 a month plus room

and board -- come in and use the computer to get better jobs elsewhere.''

For Dillon, the virtual world's economic impact hasn't been easy to spot. There is a

growing (but hard to quantify) tourism component to the local economy -- fly-fishing

outfitters, dude ranches and guides -- that's using the Web to market Dillon to the world

outside Montana. But actual e-commerce appears to be limited to a handful of individuals

selling crafts and that class of pseudo-collectible known sub rosa as ``junk we found in

the barn'' on eBay.

Wheat and fiber

Bakers thrive with little bandwidth

When it comes to using the Net as a business tool, the most conspicuous model is the

Great Harvest Bread Company. Pete and Laura Wakeman, a pair of late-model hippie

capitalists originally from Connecticut, founded the bakery in 1975 and then switched from

making bread to franchising bakeries three years later. Today Great Harvest is a closely

held empire of 140 bakeries in 40 states, with $60 million in annual sales.

|

|

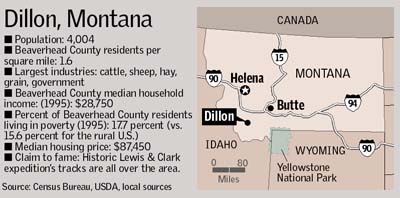

| The Internet is literally

changing the face of the rural West, as shown by this billboard on Dillon's main street. |

|

Franchising is a quintessential information-intensive business, one that's usually run

on the old command-and-control model from headquarters. Great Harvest, on the other hand,

is largely a network of peers. Seven years ago, that network began moving away from

newsletters and telephones to computers, first over the CompuServe online system and now

via the Web and e-mail. Today three of the 27 people in the Dillon home office work in Web

operations.

``We teach people how to set up and run great little whole-wheat bakeries. Think of us

as a for-profit university,'' says Great Harvest Chief Operating Officer Tom McMakin. It's

not a purely virtual corporation but rather a brick-and-mortar company with a virtual

strategy at its core, he explains. As owners share information from recipes and training

advice to marketing strategies, the private Web site's discussion archives are slowly

growing into the institutional memory of the organization. ``What we've done is spend just

about all our energy and resources linking together a giant learning community,'' says

McMakin.

By Dillon standards, Great Harvest provides premium-quality jobs. Mining and timber

have been in decline for many years with no realistic hope that they're coming back.

Cattle ranching, grains and hay -- risky businesses even in good times -- are what keep

the region running. Beaverhead County's median income is 16 percent below the national

average, and it's not uncommon to see people working two or three part-time, $7-per-hour

jobs to get by.

If another Net-dependent employer offering high-wage jobs like Great Harvest were to

consider locating in Dillon today, it would probably decide to look elsewhere. Qwest

(formerly U S West), the monopoly phone carrier in town, has a critical

bandwidth shortage in the county. Because Qwest's lines from Dillon to Butte are full, the

local Internet service provider and seven other businesses and institutions endure long

waits for high-capacity T-1 lines.

Rather than invest approximately $3 million to run fiber-optic cables along the 40-mile

route, Qwest recently struck an agreement with Three Rivers, the independent phone company

in the neighboring territory. Three Rivers is extending its fiber network to Dillon and

may begin carrying traffic to Qwest's facilities in Butte as early as next month.

Staying put

Like listening to 'a tree full of magpies'

Beaverhead County, Montana's largest, covers over 3.5 million acres -- 5,500 square

miles. That makes Garth Haugland the top government executive for a territory nearly as

large as Rhode Island and Connecticut combined. The burr-cut former game warden and

wildland firefighter who chairs the Beaverhead County Commission is also the rarest of

political creatures -- an elected official incapable of spin.

|

|

|

"We're

being pushed to e-government," says Garth Haugland, the top government executive in

Beaverhead County. He says his constituents "don't want to talk to a machine. They

want to talk to that lady behind the counter." |

The chances of Haugland uttering a disingenuous word are about equal to the chances he

will show up for the next commission meeting sporting a ponytail and an earring. This

blunt, you-heard-it-from-The-Man quality has earned him the grudging respect of some

rather diverse audiences. When 30,000 New Age vagabonds tripped into Beaverhead County for

the Rainbow Family Gathering this summer, the Rainbows -- no fans of authority figures --

christened him ``Big Dog.''

Haugland, not the type to be easily pushed around, is feeling some pressure these days.

He says the pressure to take Beaverhead County government into the Internet age is not

coming from his own constituents. ``We're being pushed to e-government, being pushed

nationally and by the Montana Association of County Officials,'' he says. ``I've talked to

a lot of people who come in here and want some information. They don't want to talk to a

machine. They want to talk to that lady behind the counter. Now how are we going to do the

Internet if we can't even get the phone system to work? That's reality.''

|

|

| Garth "Big Dog"

Haugland, left, chairman of the Beaverhead County Commission talks with a constituent at a

county commission meeting. |

|

What has the Internet really meant to Dillon? ``I don't know,'' he says, shaking his

head slowly. ``I don't deal much in that. Nellie Bandelier, she gets to chattering like a

tree full of magpies over this stuff and I tend to mentally tune her out.'' Haugland tried

a computers-for-dummies course once at the college. ``Within an hour, I was so far behind

I excused myself and didn't go back,'' he says. ``I honestly don't have an interest in

it.''

Talk in the commission chambers turns to how the children of Dillon, raised with

computers in the home, will be natives in the digital world whereas their parents shall

always be immigrants. Big Dog lets fly with a fat stream of chewing-tobacco juice and

gazes out the courthouse window toward downtown. ``I don't plan to immigrate,'' he says

flatly.

Pace of change

Slow is faster than `not in my lifetime'

Haugland's jaundiced view is probably the majority sentiment in Dillon. While a

significant contingent of their neighbors is on the Net -- about the same proportion as

anywhere else in rural America -- many people here don't see any relationship between

digital technology and their lives.

What's behind the ambivalence? First, this has always been a place where the pace of

change is somewhere between slow and ``not in my lifetime.'' Farmers are still divided

over the switch from rectangular hay bales to round. And there are a lot of people who

moved here for what Dillon isn't. It isn't Silicon Valley. It isn't Seattle. And it isn't

the kind of yuppified, BMW-driving Boutique Montana scene that many believe has ruined the

Bitterroot Valley.

The real network infrastructure of Dillon has nothing to do with the Net. On a busy

Friday night at Las Carmelitas, you could spend 10 minutes getting from one side of the

one-room restaurant to the other. That's about what it takes when every other table is

occupied by a neighbor, a client, your sister's bridesmaid from 20 years ago or that best

friend from third grade. In Dillon, network access means you get the real estate and

cattle news first -- from an old man sitting in a muddy pickup truck in front of the post

office. This is a place where you ask for a phone number and they give you four digits. If

you don't know the missing ones by heart, then you don't have network access in Dillon.

``A lot of folks who live here do so because it is the way it is, and they don't want

to see that change,'' says Dillon-Net volunteer King, an Indiana native. ``A lot of people

are afraid this computer technology is just going to bring in a lot of stuff that they

moved away from -- hectic lifestyle, high stress. Folks here don't want it. People here

are certainly not backward, but I do think they're cautious as to what's brought in. What

they're really guarding is the quality of life.''

Nobody in Dillon knows more about cultural barriers to new technology than Frank Odasz,

the Johnny Appleseed of community networking. The former oilfield roughneck and dude ranch

manager founded the legendary Montana education network Big Sky Telegraph in 1988 and

spent the next 10 years delivering training over slow 2400-baud modems to rural educators

in more than 100 one- and two-room schools.

These days, when he isn't preaching self-empowerment and digital culture to

marginalized groups ranging from impoverished youths in Mississippi to Eskimo communities

above the Arctic Circle, he's here in Dillon.

``The general mentality is that the Internet is a time-wasting toy, best suitable for

kids,'' says Odasz. ``There are real-world issues -- cutting alfalfa, water shortages,

forest fires -- and the Internet doesn't address the physical realities of what most rural

life is about. People need to see models that relate to them and are replicable for them.

``The idea of sitting in front of a computer from 8 in the morning till 5 in the

evening sounds like the death knell to the lifestyle and sense of personal pride these

people have,'' he says.

Even if a dozen Web-based companies lined Dillon's main drag, cattle, alfalfa and hay

would still be the foundations of Beaverhead County for a long time to come. Four years

ago, John Maki, the county agricultural extension agent, teamed up with Barrows and Odasz

and convened a town meeting to explain how the Net might enhance the lives of Dillon

residents. Today, Maki guesses that 20 percent of the ranchers are on the Net. Most of

those who have computers, he says, are just using them for record-keeping.

Beefalo B-to-B

Silicon Valley mindset in Big Sky Country

If there is one person who has a fighting chance to break through the agricultural

world's indifference toward all things Internet, it's Rebich, the fourth-generation

rancher with one boot firmly planted in the proud traditions of Old Dillon and the other

in cyberspace.

|

|

|

Fourth-generation

Dillon rancher Paul Rebich works in his hayfields. |

He isn't killing time, waiting as the reins of the family empire gradually pass into

his hands and those of his brother. Rebich, an entrepreneurial soul who would be right at

home in the venture-cap jungle of Silicon Valley, has other things on his mind. There's

the set of cabins he'd like to get going to capitalize on the world-class trout streams

that pass through his land. And there's his own business, Big Sky Beefalo.

Rebich figures beefalo, a cattle crossbreed containing three-eighths buffalo genes, is

just the ticket for health-conscious carnivores who will pay premium prices for super-lean

meat. Instead of selling his small herd for slaughter, he wants to concentrate on

developing superior bloodlines and selling stock, embryos and frozen bull semen to other

breeders. And the key to marketing the breeding venture is www.beefalobeef.com.

|

|

| Paul Rebich and Tina Morris, his

sister, monitor e-mail from potential buyers of their family's beefalo. |

|

The no-frills site, designed by Rebich and his wife, Kimberly, is as much a learning

experiment as it is a commercial venture. While the Internet amounts to less than 1

percent of his total annual revenues from beefalo, traditional cattle and hay, fully 80

percent of the breeding business is already coming from the Net.

The biggest international response so far is from Australia. ``That's a tough, tough

country,'' Rebich explains. ``The cattle have to be very hardy. Beefalo is very

interesting to them for that reason.'' It's entirely possible that the small herd grazing

on Rebich land five miles south of Dillon will eventually be the primary genetic stock for

most of the beefalo in Oz.

Rebich is not the only rancher dabbling in beefalo -- and that may lead to his next

venture. There are between 200 and 300 beefalo breeders around the country and today they

keep in touch through two large registry organizations. It's Rebich's hope to someday

organize them into a Web-based marketplace and registry. ``Most of those people are still

in an agricultural frame of mind. I'm stepping out on a limb a bit to do the

registry online and try to connect those breeders,'' says Rebich, ``but I believe in the

long run it's going to help my operation.''

|

|

|

Paul

Rebich tells visitors to his Web site that he wants to keep alive the business his father

and his Uncle Phillip, right, ran in Dillon. In addition to raising cattle, the family

tends to fields of hay. |

As Rebich squires a visitor across the marshy fields in his pickup, he runs through

where he's going and where he wants to be -- all the angles, all the possibilities out

there just waiting to be tested. Beefalo or not, you just know this guy isn't going to

rest until he finds a way to come out on top.

Wide open future

Dillon will change as much as it wants

In terms of a digital future, Dillon is holding some winning cards -- Dillon-Net is a

nationally renowned success story, as is Great Harvest Bread Company. Every day Judy

Halazon and a legion of other volunteers are using the Net to give some of the most

isolated people in the country small comforts most of us take for granted.

While digital culture slowly weaves its way into the fabric of daily life, it hasn't

overwhelmed Dillon. Nor has it threatened the proud ranching culture that came before.

Indeed, as much as it may vex an outsider to admit it, much of old Dillon is working just

fine without the Net.

Contact David Plotnikoff at plotnikoff@sjmercury.com or (408) 920-5867.

Photos by Pauline Lubens, Mercury News staff

photographer.

Posted October 29, 2000.

![]()